Editor's Note: On November 11, the International Conference of Mountain Tourism and Outdoor Sports (MTOS) 2025 commenced in Guiyang City, Guizhou Province. With the continued theme "Integration of Culture, Tourism and Sports Presents a High Quality Life," this year's Conference featured a series of events including the International Mountain Tourism Alliance (IMTA) Annual Conference 2025, the International Mountain Tourism Promotion Conference 2025, a Field Trip to Guizhou Mountain Tourism Destinations, and the Bank of Guizhou·Mountain Culture, Tourism and Outdoor Sport Equipment Exhibition. Over 350 participants gathered, including representatives from international organizations, government and tourism departments of relevant countries, diplomatic missions in China, tourism-related enterprises, mountain tourism destination management agencies, experts, scholars, and media from more than 30 countries and regions. They explored new pathways for the integrated development of "Mountain Tourism +", shared new achievements in mountain tourism development, and worked together to build a prosperous new future for mountain tourism. Li Shuanke, President and Editor-in-Chief of Chinese National Geography, made a presentation at the 2025 International Mountain Tourism Promotion Conference.

The following is the full text of the presentation:

Distinguished guests, friends who love mountains, delight in nature, and enjoy hiking across diverse lands,

Good afternoon! For all of us, there is a common theme that drives our perseverance and perpetual longing — the distant horizon. At the heart of every journey’s anticipation lies precisely the difference between that distant place and home. If the faraway were no different from home, no one would feel compelled to travel. Thus, the essence of travel is to discover difference, to satisfy our curiosity and thirst for knowledge. Just like when I went to Antarctica in my thirties and witnessed, for the first time, seven or eight suns shining simultaneously, it suddenly struck me that the Chinese myth of "Hou Yi Shooting Down the Suns," familiar since childhood, was not unfounded. Among the billions of people on this planet, with no reproductive isolation or racial breeding barriers, those legends passed down for millennia, across generations, must hold natural truths within them.

Today, I would like to take "The Beauty of Mountains" as my theme and introduce to you the boundless imagination — even the reanimation of perception — that those miraculous mountains across China’s 9.6 million square kilometers of land and over 3 million square kilometers of maritime territory bring us.

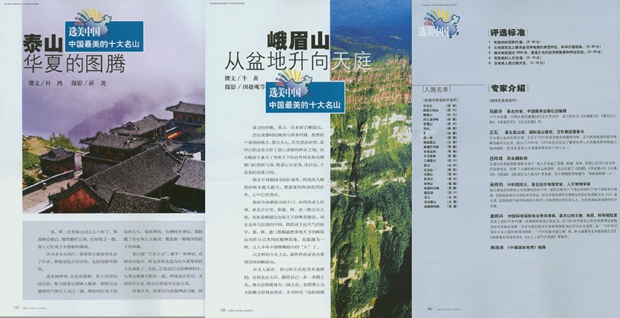

Beauty inherently has no standard. As the great philosopher Rousseau said, whether it is beauty of comfort, structural beauty, or beauty that does not cause aversion, there is no single definition. The Chinese reverence for the beauty of mountains and waters has endured for over five or six hundred years — "The wise find joy in mountains, the benevolent find joy in waters" — we place the beauty of landscape in the realm of the "purest and most pristine." Six hundred years ago, Mr. Xu Xiake left us with the judgment: "Having visited the Five Great Mountains, no other mountains need be seen; having visited Mount Huang, even the Five Great Mountains pale in comparison." This was perfectly understandable for his time: a great traveler, relying solely on his own feet to trek across most of China and pen an immortal work — that in itself was a miracle. Yet I cannot help but wonder: had Mr. Xu Xiake seen the extreme high peaks, snow-capped summits, and glaciers back then, would he still have held this view? This is not disrespect towards our predecessor, nor is it to belittle the beauty of Mount Huang. Mount Huang holds a supreme position in China’s mountain-appreciation culture and even in traditional Chinese culture. Chinese landscape painting, landscape poetry, traditional music, the timeless verses of Tang and Song poetry, 80% of Qi Baishi’s works — none are unrelated to mountains and waters, or were born in seasons graced by their presence. It is precisely because of this that these cultural treasures have been passed down through generations without fading.

More importantly, Mount Huang gave birth to the art of "leaving blank space" in Chinese painting — not filling the canvas completely, leaving room. This aligns perfectly with the cultural philosophy and logical thinking the Chinese have upheld to this day: in all endeavors, leave room; leave space for future generations to annotate and expand upon. Beauty is hard to define in a single sentence, but ugliness can achieve a human consensus. We might not articulate exactly why something is ugly — it could be the language, the attire, the expression, or the color composition of a place that makes us uncomfortable — but the feeling of "discomfort" is shared. Therefore, if beauty has no standard, then its most fundamental function is simply to make you and me feel comfortable — things that bring comfort are beautiful and good.

Mountains hold extraordinary significance for the Chinese. The reverence expressed in "looking up to high mountains with awe" and the praises sung in poetry and music all attest to this sentiment. From a global perspective, approximately 33% of the Earth’s land area is mountainous, while in China, mountains account for nearly 70%. We possess not only low and mid-elevation mountains but also miraculous extreme high peaks. In the decades before the Chinese people prospered, mountainous areas were often associated with poverty and backwardness, evoking fear. Meanwhile, the West had long developed mountains into tourism destinations, establishing mature paradigms for mountain sports and exploration. Yet China’s uniqueness lies in possessing the world’s most complete range of mountain systems and types: besides conventional mountains one looks up to see, China also has two vast regions where one must "look down to behold" mountains — on the Loess Plateau, locals will guide you to look down upon the intricately eroded landscape of gullies and tell you that is the "mountain," a phenomenon found nowhere else in the world. China also boasts mountains that defy conventional natural laws, such as those in the Three Parallel Rivers region and the Hengduan Mountains, where riverbanks lie barren while trees thrive at higher elevations. The mountains of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau are even more wondrous — where "a single tree can embody a year’s cycle, a single glance can take in four seasons" — nature’s gifts forever exceed imagination.

Within the extreme peaks of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau lie scenes that overturn our everyday understanding: in the depths of the Altun Mountains and Hoh Xil, scorching mud—reaching temperatures of hundreds or even over a thousand degrees Celsius—can erupt directly from glaciers. We all know that glaciers can scarcely survive above freezing, yet nature never adheres to human will or knowledge as its standard for existence. All of this, for those who love mountains, delight in them, and yearn for distant horizons, undoubtedly holds a powerful allure. It constantly stimulates a thirst for knowledge and curiosity—which is precisely the core charm of the distant unknown.

As a scientific media organization rooted in science and expressed through art, National Geographic China has, over the past 30 years, brought two significant insights to the Chinese public regarding the understanding of mountains:

First, it has revised our inherent perceptions of famous mountains. This is not to negate the wisdom of our ancestors. Rather, in this era where we can travel a thousand miles in a day and communication is highly advanced, we are already capable of using modern means to become “superhuman couriers” possessing “clairvoyance and clairaudience.” At this very moment, by opening a cell-phone, one can see colleagues at the Great Wall Station in Antarctica and hear the roar of wind and snow. If we still cling to the acknowledge formed 600 years ago by measuring the world solely on foot, it is clearly out of step with our times. Therefore, to truly appreciate mountains, one should look to the extreme high peaks—they bring a shock that lasts a lifetime, an objective existence previously unimaginable.

Second, it has redefined the value of mountainous areas. Mountains were once barriers: from the era of cold weapon through World War II, they served as natural shields. In the early days of peace, they hindered economic development. But today, their value is entirely different. In many regions of western China, not only does natural vegetation distribute according to vertical elevation, but different ethnic groups also inhabit distinct altitudinal zones. With every 500-meter increase in elevation, one encounters different ethnicities, lifestyles, farming methods, attire, and languages. This constitutes a rich blend of nature, culture, history, and the present.

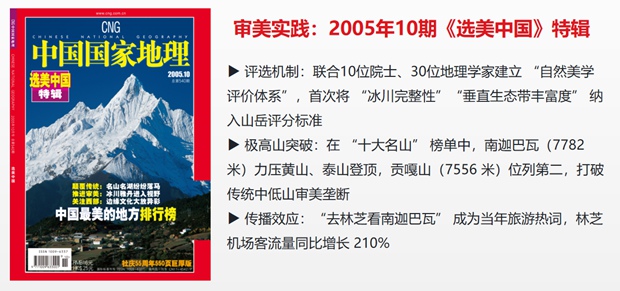

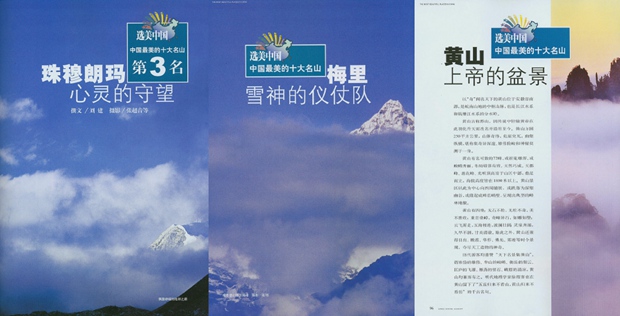

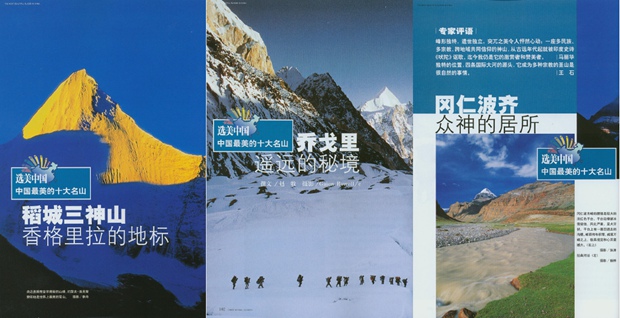

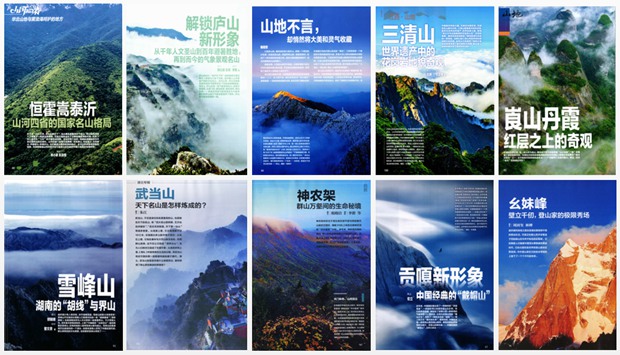

We have never been complacent or confined to inherent perspectives. Instead, with advancements in economy, culture, and technology, we continuously iterate our cognitive and standards of natural beauty. Beauty is fluid, never invariable. When I was young, what was admired was a robust, even “broad-shouldered and thick-waisted” ideal of beauty. Today, health has become the mainstream aesthetic. The same applies to our views on nature. Twenty years ago, we offered new interpretations of China’s Top Ten Famous Mountains. Just this past October, we re-examined mountainous areas from a modern scientific perspective, with a “God’s-eye view.” The reanimation and visual impact witnessed far surpass the experience of observing from ladders or helicopters two decades ago. These discoveries have also fueled a strong public demand for mountain tourism.

Today, taking this opportunity, I would like to share with you National Geographic China’s perspective on understanding mountains and our standards for the beauty of nature.

Thank you all for listening! I wish this conference complete success, and I wish all friends who have come from afar a pleasant stay in Guizhou! Thank you!

All other images provided by: Chinese National Geography

This text is translated from the conference transcript.

Editor Ⅰ: Zhang Wenwen

Editor Ⅱ: Bao Gang

Editor Ⅲ: Liu Guosong